Culture is only three things

Leaders, structure, process—a gross but helpful oversimplification.

Leaders, structure, process—a gross but helpful oversimplification.

“Let’s not pretend the people in this room aren’t the ones who can change things.”

I once found myself in a room full of powerful, brilliant executives—each representing a vital part of a multibillion-dollar business. Together, we reimagined the future of their company, laid out a strategy to bring it to life, and crafted a bold set of initiatives to get them there. People were excited, until they weren’t. One by one, every one of them got stuck. The obstacle wasn’t competitors or profitability. Operational complexity or technological feasibility. It was culture. Quickly, the room and the tone shifted from what could be—to the fear that this kind of thing would never work. Not in their culture. Until someone spoke up, “Let’s not pretend the people in this room aren’t the ones who can change things.”

It’s easy—and as that executive pointed out—convenient to think that culture is invincible. To make it a scapegoat. “Culture eats strategy for breakfast” the saying goes. But culture is malleable. It can be predicted, designed, and reinvented. It’s not mystical or mythical. We know what it is. Simply put, culture is the phenotype of 1) the personalities of a handful of leaders 2) the organization’s structure 3) the processes that define how work gets done—and who does it. That’s it. We can all go home now, unless you aren’t convinced.

Leaders and the cosmic soup of personality

Punctuality. The dress code — or lack there of. Working late versus leaving at 5PM. Being vulnerable. Being professional. Responding to emails on the weekends. Transparency. What gets celebrated — and what doesn’t. Leading with logic, versus empathy, versus vision. The type of drinks in the fridge.

Perhaps more than any other factor, culture is a reflection of a handful of leaders’ personalities. Each quirk, each idiosyncrasy, the good behaviors and the bad behaviors, their deeply held beliefs — it’s all culture. “80% of your culture is your founder” says First Round. True for startups, also true for everyone else.

Which leader(s) shapes the culture? Depends. Is the founder still involved? How many acquisitions have there been? How many offices are there and where are they? How much autonomy does each business unit, region, or function have? Your answers to those questions is the difference between a handful vs. a menagerie of leaders molding the culture. So leaders , if you’re reading, what are the behaviors you’re known for? Proud of? Disappointed by? Keep an eye out, your team—and the culture—are mirroring them.

Structures, hierarchy, who has power—and who doesn’t

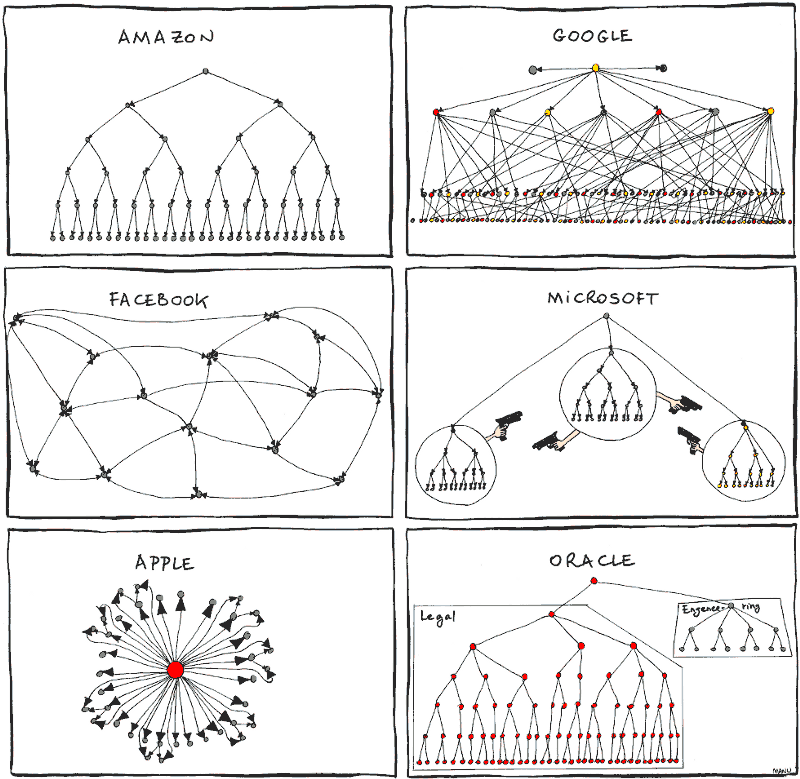

You can tell a lot about a company by simply looking at how they organize themselves. Like looking at an MRI, an organization’s structure tells you how healthy they are (or aren’t). Those boxes and wires reveal power dynamics, organizational silos, areas of specialization, and degrees of autonomy. They can expose—if not predict—afflictions, inefficiencies, and dysfunctions within the organization.

Imagine the CEO of a global software company. Does she have business units or regional offices reporting to her? The former, and you have a culture led and shaped by headquarters. The latter, and you have precisely the opposite, with each region having it’s own culture — and headquarters struggling to keep them from going rogue.

The top-down, “get in line and do as I say” cultures of Apple and Amazon are designed to deliver near-impossible levels of engineering perfection and execution speed respectively. Contrast that with Google’s famously decentralized organization structure—and the autonomy, empowerment, and innovation it enables. Look closely and you’ll see that when we talk about organization structure, we’re talking about power. And that’s precisely why structure shapes culture—because they determine how power flows throughout an organization. Take a look at your own org structure; who has power, and who feels powerless?

In theory, it’s about incentives. In reality, it’s about process.

I used to think that carrots and sticks determined how work gets done. Incentives drive behavior, which drive work and drive culture. You want something done fast? Incentivize it! You want more satisfied customers? Incentivize it! You want more sales? Incentivize it! You want less defects? Incentivize it! What you measure and incentivize (as well as what you don’t) becomes the culture. Logically, it makes perfect sense.

I couldn’t have been more wrong…

We should create processes by (1) seeking to define the metrics that matter, (2) asking how best to incentivizes them, (3) and then design a process. But it never happens that way, and that’s certainly not how it’s done at your job—is it? Didn’t think so. I’ve worked with 50,000 person corporations, and 10-person startups. I’ve worked on post-merger integrations, and designed entire functions from scratch. No matter the size or stage of growth, no one creates processes by asking “what should we incentivize?” Process just happens. You get your first customer, ship your first product, get your second round of funding. IPO, expansion, acquisitions. You end up with a patchwork of processes. Quickly made and remade. At best, incentives are a post-rationalization of the processes you’ve grown up with. It’s processes, not incentives, that define how work gets done. And it’s the processes that shape the culture. Still not convinced? Think about your expense policy. The extent to which it’s cumbersome, stress-inducing, or big-brothery is a proxy for how much autonomy, empowerment, or trust exists within the culture. Performance reviews are another hot spot where process shapes culture. I worked at Accenture during the days of forced rankings, which awarded among other things bonuses and promotions on a curve. If a project happened to have 2 consultants who were top performers, forced distribution meant 1 of them had to be given a lower grading. So it’s no surprise that (while I was there), Accenture’s culture was fiercely independent (and at times cut-throat). They’ve since abandoned forced ranking.

Do you know the names of their children?

Having a good work life means making sure the people around you are happy and stick around. There’s always going to be a more enticing job. Better salary. Better hours. A shorter commute. That same multibillion-dollar company from the beginning of this article? During orientation, new managers are asked if they know the names of the spouses or children of those on their team. The guy at the front desk. The woman in accounting. Their executive assistant. On a PowerPoint slide, a stock image of a young child appears alongside the question every new crop of leaders is (rhetorically) asked: “Do you know the names of their children?” It’s shorthand—and a reminder—to take the time to personally get to know the people you work with. What they truly care about and are working towards—their family, their next big vacation, etc.

A culture of compassion, curiosity, and empathy is an intention that must be set by those who carry the most influence. And in most companies, that’s leaders. How you set it, and make sure it sticks, comes down to processes and structure.

Leaders, structure, process, the secret to a truly exceptional culture.

A special thanks to Natasha Ouslis for being my editor, my thinking partner, and my provocateur. And thank you to the friends and colleagues who gave me feedback—you’re a bottomless well of patience and generosity. And thank you Meaghan Lynch for that inspirational spark.